Would you save a life for 100$? Should you?

First book-review - in English about the German book "Why it's so hard to be good"

This book is part empirical studies - How many people care about the life of a mouse, how they solve the trolley problem in real life, how much they work if you trust them vs. control them, how much impact a friendly mentor has on kids and many more. Most studies done by the author himself, who is a highly decorated professor for behavioral economics at university Bonn. When I saw it in the library, I took it. Obviously. Glad I read it, glad I did not buy it. Here follows why:

A) fascinating studies, I’ll give you:

The trolley or: Kantians are no Cants (sic)

A tale of two lotteries or: Why you should - maybe - not save a life for 100 $

The evil market - if you look hard (and care for mice)

The angel mentor - turning boys into girls, for a while

B) The “good” economist against markets, poor workers and reciprocal altruism

Oh, and one good advice: if in any hurry, just read 1+2. Much shorter and more relevant for your life. After that, it’s mostly me ranting about “silly” Armin Falk. Who actually is a brilliant economist.

The trolley in real life

We all know the famous trolley question: “Would you turn the lever to save 5 people from a rolling trolley - killing one person on the other rail?” - and that around 3 in 4 would. Falk et al. did a real life version “the first worldwide” (p.111): The participants were informed, that a) the institute had earmarked a donation of 350€ (nearly 400 $) to save the life of an Indian in Uttar Pradesh (paying for the treatment of 5 Indians suffering from tuberculosis, which should save all of them - else 1 in 5 would die). But the institute would cancel that donation and instead donate 1050€ to treat 3*5 people in Bihar. Thereby preventing ca. 3 tuberculosis deaths. (I assume, saving 5 - as in the original thought experiment - would have broken the budget.).

The institute took great care to make the participants understand this was REAL. And it was. There was a control group who was presented with the same moral conflict, but as a thought-experiment. ‘Boring’ result: People did decide the same way: 3 in 4 ‘pulled the lever’ - fine utilitarians - and 1 in 4 did the deontological thing: “It is always wrong to make a human die, even to save others.” - Indeed, why should there be a difference? But sure, good to know there is none. Interesting result: Both utilitarians and Kantians decided likewise on other moral questions and real situations (one was: “Here are 20 Euro, how much you wanna keep and how much you will donate to XY” - both donated on average one third.)

Anyways, great to see the institute’s money used to save many lives! Their studies paid for the tuberculosis treatment of 7145 people - saving probably around 1200 lifes and more. The first such study went thus:

Would you save a life for 100 €? How many would?

Or as the study put it: “Choose Option A and we transfer 100 € to your bank-account. Or Option B: No extra money for you. But we will donate 350 € to save a life.” (followed by information about the tuberculose-treatments). What would you choose?

So, how many choose B over A? (Assume, the German participants believed in the options - because they did.) Write down your opinion. Or say it loud and clear. Now, you may check the footnote.1 (Take note: the 100 € were promised not in cash right now, but as a bank transfer in a week or so.)

Should you save a life for a hundred bucks?

Falk looked for more ways to save lives and advance science+his career, too.

He let people choose a lottery: A “gute/good Lotterie” where chances were 60% for “institute donates 350” and 40% for “you get 100”. Or a “böse/evil” lottery, where those probabilities were switched to 40% resp. 60%. As a diagramm:

The question this time was not, how many would choose which option (same percentages as in the first study, just saying), but how they would feel about the results. Other studies claimed, donating gave a warm buzzy feeling; but those studies were a) short-term and b) people decided the outcome - were they happy about actually helping or happy about showing their good heart? Now, they “only” decided about chances. Falk found, all participants got that warm buzzy feeling, when a life was saved (all scored higher on self-reported happiness). But that feeling was weak (“extrem klein”). Even merely choosing the “good" lottery was correlated with a little higher happiness-score. As expected. But 4 weeks later, the participants were asked again, how they felt about the results of their lottery:

All felt WORSE if their lottery had ended in saving a life. Even those who had chosen the “good” lottery! Those who preferred the “evil” lottery where their chances of winning had been higher, were in even worse mood, obviously. But those who won the 100€ instead were ALL markedly happier about the outcome, even those who had gone for the “good lottery”. As Falk explains, those had it best: they got the warm vibes from being a good person, by choosing the “good” lottery. AND they got the money: “Die beste aller Welten!” (p.123)

Maybe I should be less surprised: There are “welfare”-lotteries that donate a larger share of their profits to “good causes”. Even El Gordo does. If you instead played a standard-lottery, you might get better chances for higher jackpots. Now, are you happier when you win any of those lotteries - good/evil - or when you don’t?

Falk feels more: If you help others to feel happier or be better of - then it is not altruistic, really. If we give up something, and it really feels like a sacrifice and does hurt: then we are altruistic (see p.29). Hmm, I shall return to this.2

The evil market - who cares for men or mice?

When reading Milto or David Friedman, Bryan Caplan or even just Tyler Cowen, one may believe that economists like markets. Even those big, globalised real ones. Not just the garage sale down the road. Falk seems not one of those. But he managed to talk to PETA (the militant animal-rights org) and have them agree to save and not to save mice destined for the gas boxes. (Mice sold for experiments, but were not needed.)

In a first study, participants were asked to do an IQ-test with 52 items, one group was told it were “just a questionnaire”. Both groups were told: For each correct answer, the chance that a mouse will be killed will rise by 0.9%. With drastic descriptions, pics of a little mouse and an execution video thrown in. Frank hints in the book, money was offered for right answers. His main point is: Those who thought it was an IQ-test gave 22% more right answers, instead of just marking: “don’t know”. He explains this with “The pleasure of skill” (one of Jeremy Bentham’s 14 pleasures).

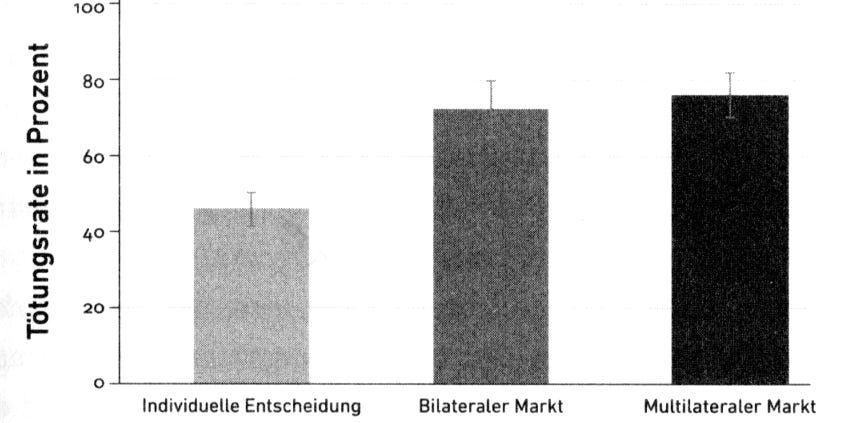

In a later series, individual participants were offered the options A: get nothing extra or B: get 10€ extra and have a “young, innocent” mouse killed. When alone, half “acted morally” (p.199; I would call it “acted in a combination of silly and misguided under pressure) and took option B (46%). Then groups of eight had to decide, each member individually and not knowing how the others would vote, but knowing that the 8 mouses would be saved only, if each of them choose option A. In no group did any mouse survive then. Obviously, I’d say. Interestingly, only 60 percent of each individual participant in those groups of eight did actually vote “kill mouse, take money”. Remember: Even when one was pivotal, it already had been 54%. When asked “how pivotal” they felt during the decision, it was found that those who felt “ay, my vote will matter in less than 4% of collective votes, pretty sure those little mice are doomed anyway” voted 80% for option B: dead mouse. While those who unrealistically assumed “chances are kinda even, at least 37%, my vote will change the outcome” did usually vote at 80% for option A: no money.

What were the chances, actually? Let us assume a wise participant would believe mostly correctly(!): “Of the others, a vote to save the mouse is as likely as the other. Thus: 50% each. 50-25-12.5-6.3-3.2-1.6-0.8 - the chance that none of the others will take option B is below ONE percent.” I conclude: Only Participants too naive about human nature and/or too dumb to do any stochastics and/or easily pressured into keeping up “good” appearances are likely to save mice at 10€/head. Am I surprised so many are? Not really, and not happy, too. But Falk seems to be deeply unhappy there are not even more spineless fools with dyscalculia among us. He definitely feels the experiment shows how vastly worse we act, when we are “less pivotal”. I’d interpret the results: When we decide alone (100% pivotal) we feel only slightly less pressure to behave-as-we-feel-we-should as when we are a hundred times less pivotal.

Falk went on to show how capitalist market situations makes it all worse: first, two participants “played” (via computer) as “seller” resp. “buyer”. The “product” was the sharing of 20 Euro. The seller offered a “price” of up to 20 Euro. If the buyer bought, then the buyer was awarded 20€ minus the price. And the seller got the price. If the price was “rejected”: no deal and no money for no one that round. Falk does not tell, but one might assume prices in the range of 9 to 14 € (it is a classic version of a conditional dictator-game, nothing new). What is new, that both knew: Each deal we both agree on, will lead to the death of a mouse. - And if I may add: Each fair deal I would normally agree to, but want to reject now to save a mouse - will cost me AND my business-partner real money. A consideration Falk prefers to ignore in the book (I hope, he didn’t in the study). I also wonder why the experiment was not run as “each rejected offer, each deal that falls through will kill a mouse” … . Falk then went on with a bigger market: nine sellers and seven buyers acted together - kinda auction like. So if a seller made a offer higher than seven of her competitors, she would lose out. While the cheapest offer would be enticing even for buyers who valued a happy mouse-life at 10€. How did that work out?

So, surely, hardly any mice survive in both scenarios? At least none in the “multilateral Market”?! Well, Falk seems to feel so. But the numbers:

In the bilateral market 72% of the mice got killed - I assume some deals fell through just because some greedy sellers put their price too high. But even in the multilateral market - a buyers-market where stupid greed would clearly be a bad strategy - 1 in 4 mice survived! Bigger markets seem to be hardly a destroyer of all moral values. While Falk mourns participants in the multilateral market now seemed to value a mouse life at only 5.10 € (falling each round of transaction to 4.50 € in the last), I am surprised to see they still valued the mouse-life at all: “Sir, would you mind to save 24 lab-mice for just 264 bucks? Only 11$ a mouse! No?! - Oh, wait a sec’, I just got great news: today is 50% off day! You can save the lot for just 132 bucks! Yes, we take credit-cards!” Would you really sign that offer? Please write in the comments. I may come back to you with an even better deal! Strictly morally speaking.

The angel mentor - turning boys into girls, for a while

No, it is not about transgender. Falk’s institute organised over a hundred volunteers (mostly college students). Each took care of one young disadvantaged child, be it refugees, poor or otherwise. Spending some time with them each week, maybe going to the zoo, maybe helping with homework. Being a pro-social role-model. For a year.

Before, during and after that intervention data was collected. Also among kids whose parents had applied and qualified but were refused by chance to have a control group. (Around 300 had applied). Falk is impressed by the great impact of those mentors on the “pro-sociality” score of the kids, directly after the mentoring AND even two years after:

Well, the intervention sounds all fine to me, too. But do those numbers really look that impressive: Without a mentor the score was 100, and with (“mit Mentor”) it was just 104. Two years later, long term / Lange Frist, all kids scored markedly more pro-social - they were two years older, after all. The kids who had had a mentor two years before scored around 3 points higher. In defence of Falk - and to explain the paragraph’s title - girls in both groups score on average 4.5 points higher than boys. Making boys about as pro-social as girls - is not a minor achievement in my book, too.

Otoh: How much effect will be left after 10 and 15 years? You may research this; that Mentor-study (“Balu und du” / “Baloo and you”) is still going on, ten years after the first cohort. Falk does not tell in the book, but he seems to be still enthusiastic. Which brings us to part B.

The “good” economist against markets, poor workers and reciprocal altruism

Falk mentions in his book several other interesting experiments - including a few classics such as Milgram - and the interested reader can find them in the appendix (well, the commented footnotes at the end of the book - that’s ok). I deeply respect his work that made the institute and its sponsors (!) finance the treatment of thousand suffering from tuberculosis. A highly unusual outcome in the field of social/behavioral studies! But when he proudly declares his studies saved “hundred of mice” (p.81), I just shake my head sadly: If the cost per mouse is 10 €, the money to “save” 350 mice would have saved the life of 10 humans (according to his calculations). A win or an outrage? /I assume the cost for the mice is higher: After buying “left-over” lab-mice - for next to nothing, I assume - he must then provide them with “best-possible” conditions for the rest of their lives (ie. 2 years): “in groups with other mice, under veterinary supervision and with allergy-free nest-building material” (p. 81). I wonder how big their CO2-footprint is. And are they still fertile? … Obviously, if the experiment promises the life (or death) of a mouse, one has to deliver.

But around half of the book is Falk ranting against sweat-shop T-shirts / climate-deniers / anti-vaxxers / immoral markets / and in general the low morale of his fellow men. At first, I doubted this “behavioral economist” ever did an ECON 101. But, he did. It seems not every economist is a Sinn, Friedman - let alone Caplan.

Seriously: What is wrong with buying a “cheap t-shirt”? Oh, it was done in “sweat-shop”? Oh, the more expensive ones were done in a spa? I guess most of those were sewed in a very similar factory in Bangladesh. With a higher profit for the brand and its PR-department. Die ZEIT once wrote: How can a T-Shirt cost just 10€?! I had to laugh. I had never paid that much for a T. I us buy - new - from 1€ to 5€ - since inflation hit: 3-6. Last month I got me a six-pack Dickies for 30€, best tees I’ve ever worn. But the main point is: the workers in those sweat-shops WANT those jobs. I am sure, it is a bad job. But it must be the better choice for the worker, else he/she would choose another. It IS sad, a Bangladeshi might have only six options (including beggar/ prostitute / unpaid field-worker … ) and sweat-shop the best available. But refusing to buy that products can bring only ONE change: the workers will have to take one of the worse options. (More likely. it will change nothing; you just spent 25€ for a fairtrade shirt financing some unproductive jobs and the next whiskey-shot for that smart guy in marketing.) Jobs in developing countries are SHIT. As it was in Europe when its industrialisatíon started. But each was good enough to make people live the villages (where the landless starved in mud huts) and flocked to the factories. Good enough to make Turkish men leave their home to got to Germany to work in assembly linea (I joined them 1989 - a student job. The hardest and worst work I ever did. Well paid, double of what my next job paid. I quit. I had better options.)

Falk says, anti-vaxxers are deeply egocentric. I say they were hurting themselves, are deeply misguided, risking their health and if they do not get treated when sick with COVID: I am fine with that. More “egocentric” they are not.

Falk seems to say, it is the good and moral thing to give to beggars (in Germany, where each can get get social help and most take that - just beg on top of that) . I agree with Tony Blair, who never gave a penny to a beggar. If you give someone money because of what he does, you PAY him for what he does. Why anyone wants to pay people a premium for begging - in rich countries - I can not fathom. Oh, and if you give to blind and handicapped in India: you might just have paid them for their self-immolation; ever seen: “slum dog millionaire” - I was in India, this stuff happens. Or it happened in the 90ies, before capitalist growth finally opened ever more alternatives. Also in sweat-shops. Bangladesh is a success-story!!!

Falk told the Austrian politician, negative net costs of refugees are ok, as we pay to help - else it would not be altruistic help. I say: a) immigration can be a huge plus. For all involved, mostly for the immigrants (else why would they migrate?!). If it is immigration into the labor-market. Not if it is just immigration into social security. I am pro (more) “open borders”; because it is the moral thing to do - and also because it works wonderfully in Switzerland and Singapore. Banning useful immigration and financing illegal immigration, while hindering it to turn into the useful sort: Not my idea of open borders.

b) if there are net costs to something - they should be paid by those who want the costly action. Taking billions of other people’s tax money and spending it on one’s own pet-projects: I see nothing morale or pro-social in this. If a majority decides to do so: well, long live democracy, sure. I do not have to like those projects and will try to vote against those who want to build silly stuff and create BS-jobs by taxes.

Altruism can and should be reciprocal. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages”

―Adam Smith,An Inquiry into the Nature & Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Vol 1

“Money is a formal token of delayed reciprocal altruism.”

―Richard Dawkins,The Selfish Gene

Falk does mention some criticism, he does not mention fundamental critics of dictator-experiments. No one unrelated ever gave me an envelope with money “just because I got some, ya know”. If you find 10 bucks, will you give half to the next person you meet on the street. No, you won’t. Even the idea is preposterous. But a WEIRD college student, in a room with some psychologists and another WEIRD student - you give them 10 notes of 1 buck and ask: “How much of it you will share with your fellow man here - or to these excellent organization helping sick kids in Africa?” Well, most may give then some bucks. But that is a measure of SDB, not of their morale. Say you are an effective altruist and you give away 5% of your income to good causes: What is the moral thing to do with an extra-income of 10/20/100$ ? You give away 5% - as always. And if you give around 1% each year - then you are a fine guy , too. And giving 1$ of 100$ to the poor, is fine and well. While in Falk’s world, a guy who shares 6$ (of the 20$ he just got) to the poor in Africa is even slightly more egoistic than the (to him unimpressive) average!!! (p.115)

Actually, I would (hopefully) prefer Falk’s institute to spend 350E to fight Tuberculosis - and gladly forego “my” 100€! But I would then recalculate my donations for this year and reduce them accordingly. Because I had just done sth. good to the amount of 350! Actually in my book, that is enough doing good for more than a year - I pay taxes, have kids and I do give to some altruistic causes that are less than 100% pure altruistic; even my paid substack-subscriptions, I consider mostly ‘altruistic’ (ACX offers no extra-value for paid subscribers worth anything near 20$ - but I gladly pay my share for the good cause.)

Compare to Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis - people who get a one-time corona-bonus of 3,000€ may not all spend it instantly, but only spend more to the extent that their income of their next decade has gone up by 3k - if that income is 600k, they may feel just 0.5% “richer”.

If I really valued the life of an unknown lab-mouse at 10€ (for me personally!), or even at 5$ - I would spend heavily on animal welfare. I do not. 95% of participants in Falk’s studies do not. How Falk believes they (should) do, I do not know. But then doing his job has its own perk and causes a certain déformation professionnelle.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

―Upton Sinclair,I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked

Little more than half. 57% agreed to forego the 100 (a day’s salary on German min. wage) to save a human life. To quote the author: “(57%) Is that a lot or a little. I don’t know. It is, what it is.”

In case I did not: a) I think reciprocal altruism is fine, actually better, when possible. b) If you give at least 100$ a year to purely altruistic causes, you should go for the “donate 350” option. If you succeed, then reduce your other purely altruistic donations by at least 100 this year or mx. by 100 the next 4 years. - If you win the 100 istead: earmark 20 cent or 10% for donations that year, depending on how much of your income you usu donate per year.